Working Sets vs Total Sets: The Real Reason Your Program “Isn’t Working”

How many sets did you do today?

If you train consistently, you probably have an answer. But here’s the problem. Most people are counting every set the same, and not every set creates the same result.

That confusion is one of the biggest reasons lifters feel like they are “doing a lot” but not getting stronger, not building muscle, and not seeing their body change.

This post will help you separate two ideas that sound similar but are not:

1) Total sets (everything you do)

2) Working sets (the sets that actually drive adaptation)

Once you understand the difference, you can get more results without needing more time in the gym.

With the Iron Camp Method, we care about training that is progressive, repeatable, and honest. “Hard work” is not just showing up. It is doing enough high quality work inside the sets for your body to have a reason to adapt.

If you have ever said:

- “This program doesn’t work for me.”

- “I lift a lot but I don’t grow.”

- “I feel sore but I’m not stronger.”

This post is for you.

Total Sets vs Working Sets (Simple Definitions)

Total Sets

Total sets are every set you do in the session.

Warm ups. Ramp sets. Back off sets. Technique sets. “Let me get a feel for it” sets. The set you did while talking. All of it.

Total sets matter. They prepare your body, reinforce technique, and build structure into the session. But they do not all create the same training stimulus.

Working Sets

Working sets are the sets that actually create a meaningful stimulus for strength and hypertrophy.

These are the sets done with enough load and effort that your body has a reason to adapt.

A clean way to think about it:

Warm up sets prepare you to train.

Working sets are the training.

This does not mean warm ups are useless. It means you should not confuse preparation with the sets that drive change.

Why This Matters More Than You Think

On paper, a lot of programs look great.

The exercises make sense. The set and rep scheme looks solid. The weekly schedule is reasonable.

But a program is not just the plan. It is the plan plus the effort you put into the sets.

Most programs assume your “work sets” are challenging enough to count. If your sets live too far from failure, the plan might be fine, but the stimulus is not.

This is especially important for hypertrophy. Across a wide range of loading schemes, what consistently shows up in the research is that effort and proximity to failure matter because they help recruit more muscle fibers and create a stronger growth signal [1][2][3].

“If you finish most sets feeling like you could do five more reps, you might be practicing more than you are training.”

The Quick Test: The “Five More Reps” Rule

Here is a simple reality check you can use today:

If you finish a set and you honestly feel like you could have done five or more reps, that set was mostly practice, not stimulus.

Practice is not bad. Practice is how you get better at the movement, stay safe, and build consistency.

But if your goal is strength or muscle, you need enough sets that are hard enough to count as working sets.

What Counts as a Working Set (A Practical Standard)

Most lifters do best living in a “hard but repeatable” zone.

A simple standard for a working set:

- Around RPE 7 to 9 (about 3 to 1 reps in reserve)

- Reps are clean, but you have to lock in

- The bar speed slows near the end because the set is actually challenging

- You would not want to repeat that set again without real rest

This is the sweet spot. It creates stimulus without turning every session into a max out.

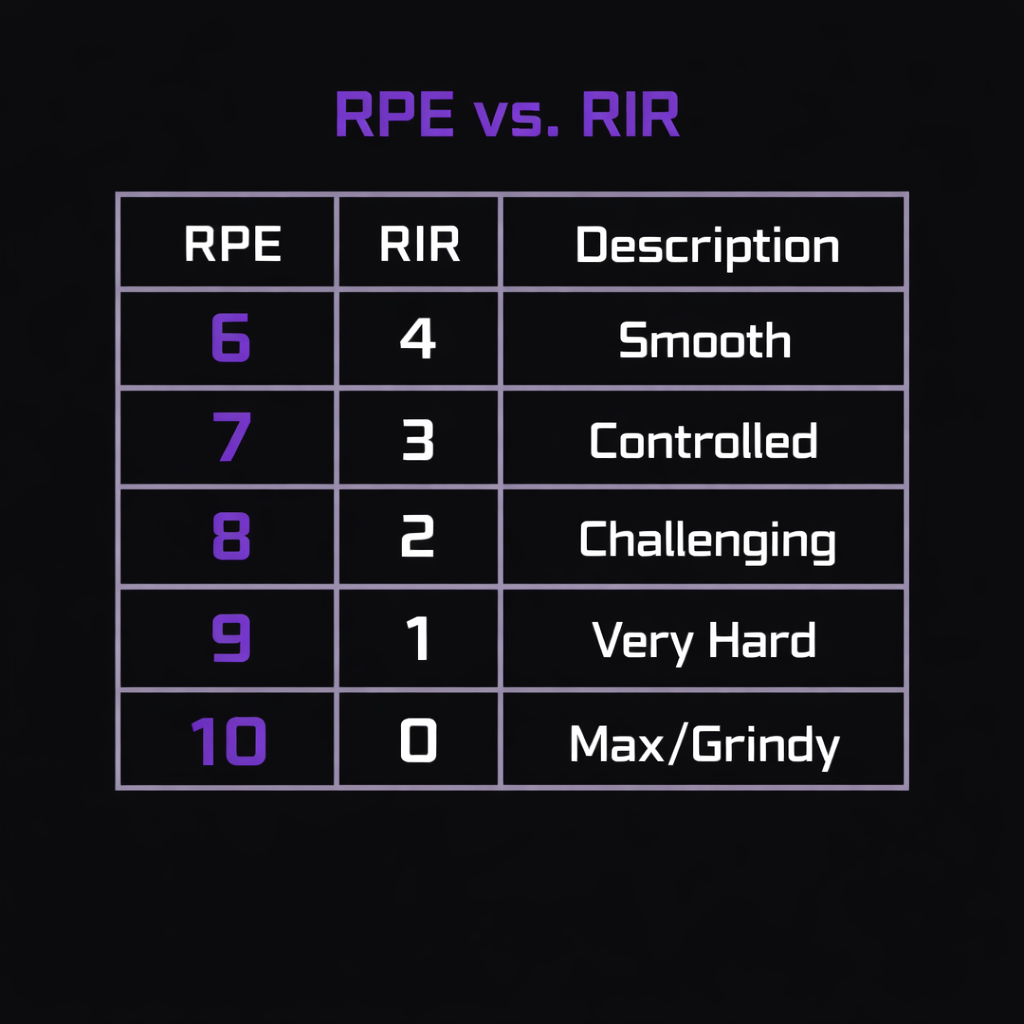

RPE and RIR Explained Like a Normal Person

RIR: Reps in Reserve

RIR is simply how many good reps you had left.

- RIR 3: You could have done about three more reps with good form

- RIR 2: You had about two reps left

- RIR 1: You had about one rep left

- RIR 0: You hit failure (you could not do another rep without breaking form)

RPE: Rating of Perceived Exertion (RIR-Based)

In strength training, RPE is often used as a “reps in reserve” scale.

- RPE 7 is about 3 reps in reserve

- RPE 8 is about 2 reps in reserve

- RPE 9 is about 1 rep in reserve

- RPE 10 is about 0 reps in reserve (true limit)

This approach is widely used for autoregulation because it helps you adjust training stress based on how you actually perform that day, not just what the spreadsheet says [4][5].

The Most Common Problem: “I Did Four Sets”

A lot of people run four sets of an exercise. Here is how it often goes:

- Set 1: feels like a warm up

- Set 2: smooth

- Set 3: starts to get hard

- Set 4: hard (maybe RPE 8)

That is four total sets.

But it is probably two working sets (sets 3 and 4).

And no, that does not mean you failed. It means you are being honest about what actually drove stimulus.

Where people get stuck is when they write “four sets” in their log, assume all four were working sets, then wonder why volume “is not enough” or why they do not progress.

If only half your sets are actually hard enough to count, your effective weekly volume might be much lower than you think.

Working Sets and Results: What the Research Supports

For muscle growth, weekly set volume matters, but it is best understood as weekly working sets per muscle group, not just total sets written on a plan.

A well known meta analysis found a dose response relationship between weekly resistance training sets and hypertrophy, with higher weekly set volumes tending to produce greater muscle growth within the ranges studied [1].

That does not mean “more is always better.” It means you need enough hard sets to create a growth signal.

The issue for most lifters is not that they are allergic to work. It is that they overcount “easy sets” as working sets, then accidentally under dose the stimulus.

Do You Need to Train to Failure for a Set to Count?

No.

Training to true failure can be a tool, but it is not required for strength or hypertrophy.

A systematic review and meta analysis comparing training to failure versus non failure found no meaningful overall difference in strength or hypertrophy outcomes in many contexts, especially when volume is similar [2].

The practical takeaway:

- You do not need RPE 10 every set.

- You do need sets that are close enough to failure to be considered a real stimulus.

For most people, most of the time, RPE 7 to 9 is where the best training lives.

Does Load Matter, or Is Effort Everything?

For hypertrophy, research suggests you can build muscle across a wide range of loads, as long as sets are taken close enough to failure [3][6][7].

For strength, heavier loading tends to be more specific and more effective for maximizing strength gains, even when hypertrophy is similar [3][7].

So the question is not “heavy or light?”

The question is “what is the goal of this block, and are the working sets honest?”

Rest Periods Can Change Whether a Set Becomes a Working Set

This is a sneaky one.

If you take short rest periods, your next set might feel hard, but it is sometimes hard for the wrong reason. You are limited by fatigue, not by muscular output. That can reduce performance, reduce reps, and turn later sets into low quality grindy work.

A study in resistance trained men found longer rest periods (for example, about three minutes) led to greater increases in strength and muscle thickness compared to shorter rests (about one minute) when training volume was otherwise similar [8].

There is no universal perfect rest time, but if your goal is strength or hypertrophy, you usually want enough rest to make your working sets high quality.

How to Approach Sets and Reps Inside a Program (The Iron Camp Method)

Here is the approach that keeps training honest and productive.

1) Use Early Sets to Ramp

Your early sets have a job:

- Groove technique

- Build confidence under the movement

- Prepare joints and tissues

- Let you feel the weight before the real work

Specific warm ups can improve resistance training performance compared to doing nothing or only doing general activity, depending on the approach and the lift [9].

Ramping is not wasted time. It is preparation.

Just do not confuse preparation with working sets.

2) Earn 1 to 3 True Working Sets

For most lifters, most exercises do not need five true working sets.

They need one to three hard, high quality sets that land in the target effort range and can be progressed week to week.

This is how you build a body without burning out.

3) Live in the Sweet Spot

Not every set should be maximal.

But not every set should be easy.

The goal is consistent exposure to challenging sets you can recover from and repeat.

That is the boring secret behind impressive results.

“Progress is not about how smoked you feel. It is about how many high quality working sets you can stack across months.”

How Many Working Sets Per Week Do You Need?

There is no single number for everyone. Your training age, recovery, nutrition, stress, and exercise selection all matter.

But here is a practical range that works well for many people, and aligns with the idea that more weekly sets can produce more hypertrophy when they are truly hard sets [1]:

- Beginners: 6 to 10 working sets per muscle group per week

- Intermediate: 10 to 16 working sets per muscle group per week

- Advanced: 14 to 22 or more working sets per muscle group per week (managed carefully)

Start at the low end, then build up based on progress and recovery.

If your joints are angry, your sleep is bad, and performance is dropping, you are not under training. You are under recovering.

Two Examples You Can Steal Today

Example 1: Strength Focus (Main Lift)

Goal: Build strength while keeping technique clean.

- Warm up sets: as needed

- Ramp sets: 2 to 4 sets building to a challenging load

- Working sets: 2 to 4 sets at RPE 7 to 9

- Optional back off: 1 to 2 sets if they still land as real working sets

If your back off sets are easy and you are doing them just to do them, either adjust load or remove them.

Example 2: Hypertrophy Focus (Accessory Lift)

Goal: Stimulus with joint friendly execution.

- One lighter prep set to groove pattern

- 2 to 3 working sets at RPE 8 to 9 in the 8 to 15 rep range

- Rest long enough to repeat quality reps

If you stop every set with five reps left in the tank, you did not train that muscle. You moved it.

Common Mistakes That Make People Think They Train Hard (But Do Not Grow)

Mistake 1: Counting warm ups as volume

Warm ups matter, but they are not a replacement for working sets.

Fix: Label ramp sets as ramp sets. Label working sets as working sets.

Mistake 2: Chasing fatigue instead of stimulus

Feeling destroyed is not a plan. It is a feeling.

Fix: Focus on repeatable working sets in the RPE 7 to 9 range, then add load, reps, or sets over time.

Mistake 3: Rushing rest so every set becomes sloppy

Short rest can make sets feel hard, but it can also reduce performance and quality.

Fix: Rest long enough to make your working sets productive, especially on compound lifts [8].

How This Fits the Iron Camp Method

With the Iron Camp Method, we want strength that carries over to real life.

That means:

- Training hard enough to create change

- Training smart enough to stay healthy

- Training consistently enough to build momentum

Working sets are where that happens.

You do not need a perfect program. You need a program you can execute with honest effort.

If you want help dialing this in, we can do it with you.

Want Us to Build Your Training Plan (So Your Sets Actually Count)?

If you are in Greenwich, CT and want coaching in a semi private setting, we will help you train with intent, track your working sets, and progress the right way.

If you are not local, you can train with us through the Iron Camp App powered by Trainerize.

The goal is simple:

Do fewer “practice only” sessions.

Do more working sets that force adaptation.

Build strength that lasts.

The People’s Strength Coach

References

[1] Schoenfeld BJ, Ogborn D, Krieger JW. Dose-response relationship between weekly resistance training volume and increases in muscle mass: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2017. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27433992/

[2] Grgic J, et al. Effects of resistance training performed to repetition failure or non-failure on muscular strength and hypertrophy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2022. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33497853/

[3] Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J, Ogborn D, Krieger JW. Strength and hypertrophy adaptations between low- vs. high-load resistance training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2017. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28834797/

[4] Helms ER, Cronin J, Storey A, Zourdos MC. Application of the repetitions in reserve-based rating of perceived exertion scale for resistance training. Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2016. Full text: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4961270/

[5] Zourdos MC, et al. Novel resistance training-specific rating of perceived exertion scale measuring repetitions in reserve. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2016. (PDF access may vary): https://blog.performancelab16.com/optothoa/2023/05/Novel_Resistance_Training_Specific_Rating_of.31.pdf

[6] Morton RW, et al. Neither load nor systemic hormones determine resistance training-mediated hypertrophy or strength gains in resistance-trained young men. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2016. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27174923/ Full text: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4967245/

[7] Schoenfeld BJ, Peterson MD, Ogborn D, Contreras B, Sonmez GT. Effects of low- vs. high-load resistance training on muscle strength and hypertrophy in well-trained men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2015. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25853914/

[8] Schoenfeld BJ, Pope ZK, Benik FM, et al. Longer interset rest periods enhance muscle strength and hypertrophy in resistance-trained men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2016. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26605807/

[9] Ribeiro AS, et al. Effect of different warm-up procedures on the performance of resistance training exercises. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2014. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25153744/

[10] American College of Sports Medicine. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2009. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19204579/